Driving north on Alberta's Highway 2 just before High River, you see a handwritten sign “Freedom”, with two faded, tattered and ripped Canadian flags on each side of the sign. I very much doubt the landowner who put up this display has even the faintest comprehension how symbolic it actually is.

There have been numerous articles lately about the “epidemic” of loneliness (New York state has even appointed Dr. Ruth as a “loneliness ambassador”, whatever the hell that means.) Fully one-quarter of Canadians live alone. More than half of young people in America don’t have a romantic partner, including 63 percent of men. Loneliness is bad for our health, contributing to strokes, heart disease and innumerable other mental and physical problems. It’s also bad for the economy; the US Surgeon General released a report that showed that loneliness was costing America hundreds of billions of dollars in lost productivity. And this is a worldwide problem. Family formation has plummeted throughout the industrialized world. About half of Swedish households are single person. More than a quarter of all 20- to 34-year-olds in the UK still live with their parents.

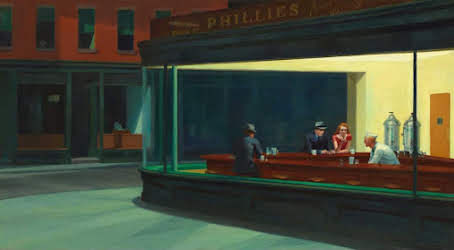

What has caused this? Technology is usually singled out first, but it really is only a part of the story. The main explanation for the epidemic of loneliness is the fact that the preeminent value in our modern societies is individual autonomy. This autonomy, which the unthinking believe is the only definition of freedom, is simply the ability to do whatever you want in the moment, even if what you want causes you, and sometimes those around you, harm. Autonomy is why liberals are for social programs and progressive taxes, arguing that poor people don’t have autonomy. It’s why conservatives complain about the nanny state dictating how people should live (of course, conservatives are complete hypocrites on this). Despite all the bickering between left and right, they mostly agree on this fundamental concept.

In 1975, Richard Thomas, an architectural historian, wrote his landmark paper From Porch to Patio. Thomas detailed the subtle yet revolutionary change that occurred with houses from the 1950s onward. Before that time, most houses had a front porch facing the street. Thomas called porches an “intermediate space”, a zone between the privacy of the home and the public street and sidewalk. Porches reflected the expectation of sociability among neighbors and other members of the community. If you were sitting on your porch, people walking by could easily stop and chat, or at the very least say hello. But patios replaced porches and moved this outdoor space to the backyard, away from the street. Now, the only people who can see you are your immediate neighbors, and they are likely separated from you by a high fence. The patio is a place for just you and your family. It is the perfect refuge for people who want to get away from other people. The enclosed privacy of the backyard patio is the complete opposite of the sociability of the front porch. You don’t ever have to talk to anyone.

This past summer, my wife and I drove up a rough old logging road outside Vernon, BC to check out the Aberdeen Columns (very cool). I marvelled that there were driveways poking out of the thick forest, way out in the middle of nowhere. You see this all over Canada, people who already live in smaller communities, moving even further into the woods for more privacy and more isolation. If they can afford it, everyone wants privacy. Living with people is hard: they make noise, they have irritating hobbies, their cooking smells bad, their cat craps all over your yard. The world is louder, busier, and nuttier than it’s ever been, so it's understandable that people want to get away from it all. (I am as guilty as anyone - no one has ever mistaken me for a friendly person.)

But when people can easily withdraw from the public space into their own private world, it slowly kills the social norms that govern how we should treat one another. I hear people complaining how rude and selfish “other” people are these days, about how self-involved and entitled people are. (The Boomers level this accusation at Millennials all the time, but no generation has had it better than the Baby Boomers.) Building beneficial social norms – trust, reciprocity, empathy – requires effort. It demands face-to-face interaction, not posting on social media, not hiding in a man cave filled with TVs and video games. It requires talking and listening and compromising. When people live close together, they have to make allowances for others’ wants and problems.

The classical conception of freedom wasn’t based on “I can do whatever I want.” Aristotle believed real freedom came about only when man was able to free himself from his own base desires and impulses by cultivating certain virtues through education, discipline and sacrifice. The ancients didn’t celebrate greed, lust, sloth, gluttony; they thought these impulses, while natural, had to be controlled. Now we have a society that instead caters to our primitive desires, no matter how destructive they are. If you want to drink, gamble, hump, eat, or shop your life away, there is always someone willing to sell you whatever you need to feed your pathology.

To satisfy all of our desires, capitalism prioritizes efficiency and convenience over the messiness of personal relationships. In large and small ways, our economic system diminishes the role of friendship and community. Want to climb the corporate ladder? You better be willing to move around a lot. Want to make good money in the Alberta oilpatch? You better be willing to work clusters of days at a time – one company I know does 7 on, 7 off - in remote locations, and then commute home on your off days. Shift work is common, and it has people working or asleep when their friends are free, not to mention the toll it takes on their overall health. And capitalism has impacted the way we relate to other people; “selling yourself” and networking often substitute for real relationships. Friendship today is frequently just transactional and ephemeral.

The philosopher Patrick Deneen has put it this way: we are lonely because we want to be lonely. We don’t want other people infringing on our space. We certainly don’t want them even gently suggesting how we should live. This militant individualism, exemplified by covid deniers and gun nuts, sees everything in terms of individual choice. There is no longer such thing as the common good, a concept that Aristotle defined as something that only a community of people acting in concert can achieve. The common good requires compromise, shared sacrifice and occasionally subordinating your own desires to those of the group. It requires engaging with other people. Without the common good, there is no community and no nation. We have replaced it with hedonistic consumption - we think we are free because we can buy whatever we want. This purchased pleasure feels good for a while but in the end leaves us empty, weak and unable to solve the biggest issues. Hedonism will not win wars, control pandemics or save a rapidly deteriorating environment.

Almost all of our problems here in Canada, and the rest of the West, are explained by the fact that we value individual autonomy over everything else. We seem to know that what we have now isn’t working; every poll shows that people believe our country, and the world in general, are getting worse. But we don’t seem to understand that we made choices that brought all of this about. We picked the patio over the front porch, and now we have to live with the consequences.

Comments