Canada's economy has been sluggish for several years, with almost all economic growth attributed to the large increase in our population since the pandemic (we went from 37 million to 41 million, roughly a 10 percent increase). A key measure of economic growth is productivity, which is defined as the quantity of output relative to the amount of inputs. The usual formula to measure this is gross domestic product (GDP) per hour of labor worked (there are myriad problems with GDP, but for now it is the only measure people use). To give a simple example, let’s say you sell cupcakes. Normally it takes you 2 hours to make 20 cupcakes. But then you figured out a better way to put on the icing, and now you can make 30 cupcakes in two hours. This would represent a productivity increase of 50 percent and it would cause you to make more money from your cupcake business. Essentially, a productive economy does more with less, which makes everyone better off.

The problem for Canada is our productivity is significantly lower than other G20 countries, particularly the US. I’ve watched assorted bank economists and CEOs go on BNN and complain about Canada’s lagging productivity, but I always come away shaking my head in disbelief at what passes for expertise in this country. Their solutions, when they offer them instead of just complaining, are always the same - more handouts to big business. The latest was the exceedingly dense CEO of RBC, Dave McKay, who blamed the current government for pretty much everything and said Canada needs “a more competitive tax structure.” Quelle surprise, he’s calling for tax cuts! The problem, of course, is he wants the wrong taxes cut - not yours, but his own.

There is a very good explanation for our productivity problem, and it comes from a real economist, not some bank lackey. William Baumol came up with his elegant Theory of Cost Disease in the 1960s. Baumol foresaw that productivity gains in manufacturing, achieved mostly through technological advances, raised wages in both manufacturing and in the labor-intensive services sector. Wage increases in the economy are mostly tied to productivity; the company you work for won’t pay you more if they aren’t making more money. In manufacturing (like the cupcake example) the relationship is clear; if a company can make more stuff at lower cost, it makes more money, and so it (begrudgingly) passes some of that increase to its workers.

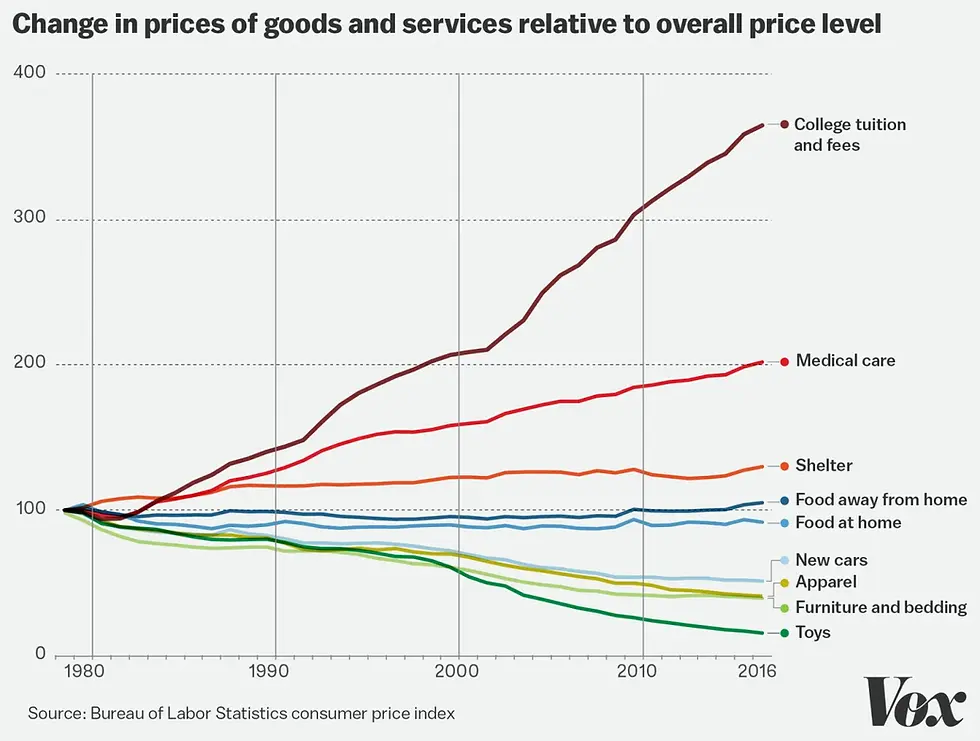

In labor-intensive services, technology has had much less impact. The wages of the people providing the service are by far the main driver of the cost of the service. But as wages rise in the “making stuff” sectors, they also have to rise for those in the service sector because all salaries are relative. People would never become teachers or cops if the salaries for those jobs didn’t keep up with everyone else’s salaries. Therefore, Baumol concluded that we should expect the real cost (meaning adjusted for inflation) of manufactured items - things like clothes, electronics, appliances, etc - to fall, while the cost of services - health care, education, child care - to increase. The data shows Baumol’s theory has been exactly correct.

Over time, more and more of Canada’s GDP has come from sectors that have low productivity. About 41 percent of GDP comes from various levels of government (for comparison, the US is at 38.5 and Germany is at 49). The biggest private sector component in our economy is housing, which is an unsustainable 20 percent of GDP. Home building is also labor-intensive because every building or house is a one-off; you can’t mass produce high-rise apartments on an assembly line. Our small size, our northern climate, our reliance on natural resources, and most importantly, our "crazy" notion that government should actually do things that make our lives better, all conspire to handcuff the Canadian economy.

In terms of government services, the issue is obvious. Functions like health care, education, law enforcement, etc. are very labor-intensive, so there is little that can be done to increase the productivity of these services. Furthermore, Canada is a large country with a relatively tiny population. The government has to provide a comparable level of service all over the country, to large cities and small towns alike. For things like health care and education, this often means getting doctors and teachers to live in places they don’t necessarily want to live, which means the government needs to pay up, usually in the form of student loan forgiveness or living allowances. Many of the services the government provides require face to face contact. Take child protection; you can’t have the social worker calling a family on the phone and asking “can you tell me if your 5-year-old son has a huge bruise on his arm?” The social worker has to be on scene, which means you need these service providers scattered all over the country. These realities increases costs and make everything harder to administer.

The solutions to this problem aren’t pretty or easy, no matter what the bankers tell us. Take health care; we need to understand that it’s not “free” and that we will likely need to pay for some services out of pocket, which hopefully incentivizes people to use resources more judiciously. And we do need tax reform, just not the kind our business elites keep whining about. We should to cut taxes on lower- and middle-class people and raise them on the wealthy and corporations, because large income inequality makes cost disease even worse - the rich aren’t price sensitive at all, they will happily pay for a private surgeon to jump the queue. We also need to stop incentivizing companies to continually buy back their own shares and instead use taxes to prod them to invest in real economic activity. In short, to increase productivity we need to raise and reconfigure taxes on capital while lowering them on labor. This sounds counterintuitive but really isn’t if you understand how the economy actually works. Most importantly, we need to take a jackhammer to all the oligopolies - the banks, telcos, grocers, etc - and allow more real capitalist competition in Canada. Competition fuels productivity like nothing else can.

It is Baumol’s theory of cost disease that explains why all those politicians- Doug Ford, Stephen Harper, Jason Kenney, to name three - who have run on the promise that they will dramatically cut the government’s budget have failed miserably every single time. Increases in the cost of government services aren’t the result of inefficiency, they are a natural by-product of a society that has become wealthier over time. Pierre Poilievre will be the next delusional blowhard to learn this the hard way. Running an advanced country for a population that demands and requires a high level of services costs a lot of money. There is no magic wand that can change that reality.

Comments